What follows is a report blog from a member of the NGI Commons consortium (Nicholas Gates, from OpenForum Europe) regarding the recent OSPOs for Good 2024 Symposium.

Open Source Programme Offices (OSPOs) and Digital Commons: Emerging considerations from the OSPOs for Good 2024 conference and beyond

A question we get frequently asked at NGI Commons is some version of this: How can governments actually invest in and support the Digital Commons agenda? NGI Commons consortium partners have observed that governments have many tools to put the interests of Digital Commons forward in policymaking and public administration. One such tool is the Open Source Programme Office, or OSPO.

Building on the learnings from the recent high-level OSPOs for Good 2024 Symposium – which took place on July 9 and 10 in New York City – this article will explore these ideas and their potential relevance for public sector support to Digital Commons.

What are OSPOs?

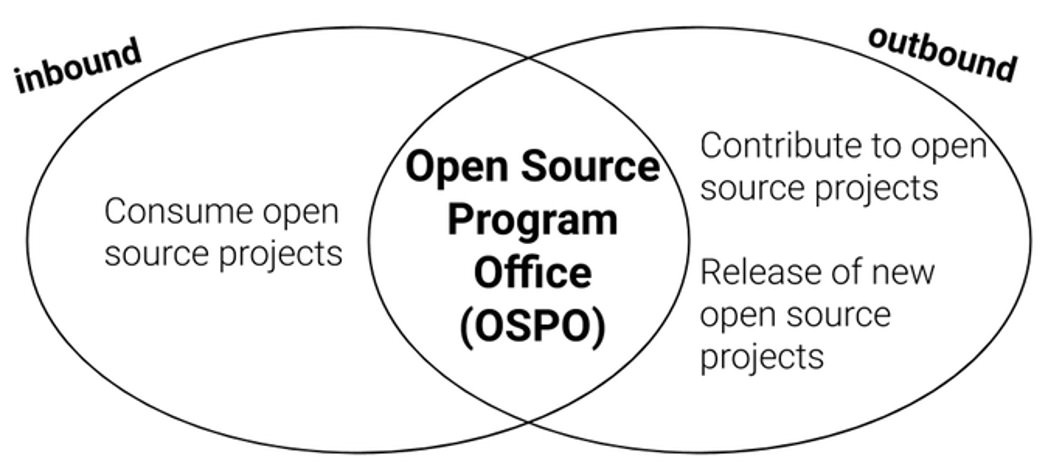

OSPOs are centres for excellence and policy coordination that support adoption of, and contribution to, open source technologies. For over the last two decades, OSPOs have been leading the way in supporting the health of open source communities and helping businesses to nurture and contribute back to them. And in the last ten years alone, they have grown in use in the public sector.

OSPOs can – in a public sector context – play an important role in helping to kickstart adoption and use – as well as contribution to – open source software and other open technologies. This is, in part, because governments increasingly feel the need to decrease dependence on a handful of vendors, create more choice in their technology options, and identify solutions which enable higher levels of digital sovereignty.

We have learned – from the examples of OSPOs in Germany, France, and other countries – that OSPOs can help address the challenge of formalising and coordinating relationships with open source communities. They have, for example, expanded the standardisation and use of open source components in digital government efforts, supported contribution to open source projects and communities, and functioned as tools for evangelising and engaging around the use of open source.

How do OSPOs support digital commons?

Part of the value of OSPOs for Digital Commons would be rhetorical. Just by thinking about open technology solutions as Digital Commons that require public sector investment and support and investment, OSPOs can help policymakers channel more resources and support into those communities. Since OSPOs help formalise and coordinate relationships with open source communities, the Digital Commons agenda would give them a real mandate to act as trusted advisors to governments and support/invest in the use of open technologies.

OSPOs can – in theory – provide ‘policy infrastructure’ to support rules and governance for Digital Commons. Just as there is ‘hard’ infrastructure like roads and bridges, ‘soft’ infrastructure like policies, regulations, and governance play a huge role in allowing a government to implement and deliver upon its policy priorities. Indeed, adopting and using open source technology more intentionally through ‘soft’ policy infrastructure – for example, the European Union Public License, or EUPL – is a priority for many governments seeking to build the ‘hard’ digital infrastructure that enables them to deliver on their policy priorities.

As a result of this policy infrastructure, OSPOs might enable norm-setting around rules and governance of Digital Commons by channelling more resources into them and creating more opportunities for checks and balances. Early evidence shows that Digital Commons projects which are self-organised – and which also have well established rules and governance models – can reduce single dependencies through distributed production (which characterise some, but not all, open source communities).

Finally, OSPOs build relationships with open technology communities and create mutually beneficial channels for exchanging technology and ideas. OSPOs might help formalise roles and responsibilities around Digital Commons being used as part of society-wide digital infrastructures. They can also help governments to contribute back to open source projects, and to work with their developers to ensure that government’s expanding expertise, staff, and funding resources are effectively leveraged in support of communities.

What have we learned from the OSPOs for Good 2024 Symposium?

This thinking was on full display at the OSPOs for Good 2024 Symposium. OSPOs for Good was co-organised by OpenForum Europe (OFE) and was attended by representatives of both OFE and Linux Foundation Europe (LFE) (both members of the NGI Commons consortium). (You can watch the recordings of both days here.)

In a thematic track on Open Source and Government, Pearse O’Donohue – a Director for Future Networks Director from DG-CNECT – shared more about European values and what Europe has to share with the rest of the globe. In his keynote remarks, O’Donohue highlighted lessons on open source policymaking from the development of the critical role of the European Commission OSPO and supporting other OSPOs. He also shared lessons learned from public administrations across Europe and advocated for investing in digital commons.

The Open Source at Work in the World thematic track also had a high degree of relevance for Digital Commons. In it, Adriana Groh of the Sovereign Tech Fund (STF) – a German public sector investment fund for open digital infrastructure – came to the front of the ECOSOC Chamber for a keynote with Andreas Reckert-Lodde, Interim Director of the Center for Digital Sovereignty (ZenDis) – an German federal driving cooperation between the open source community and German public administrations. Together, they showcased how parts of the government are coming together to support and invest in open source.

Groh – a member of the NGI Commons Strategic Advisory Panel – discussed some of the ecosystem-strengthening activities and Digital Commons which are being funded by STF’s investments, and how funding is critical for the health of Digital Commons. Reckert-Lodde, on the other hand, showcased the work ZenDis is leading on engaging the open source developer community. He reflected on the process of making open source code development both feasible and desirable from the perspective of public administration and public service delivery.

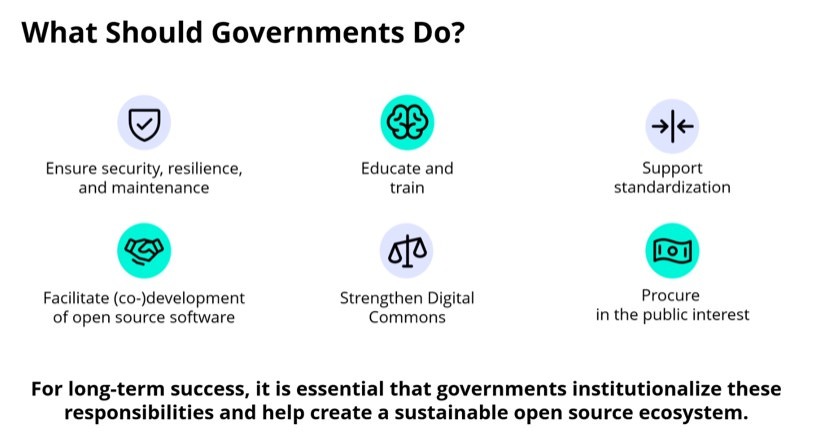

Both the STF and the ZenDis are strong examples of how to invest in and govern Digital Commons. By focusing on principles of co-development and contribution, as well as working to strengthen education and reform procurement regulations, both institutions function like OSPOs in some regards and are creating the preconditions for using Digital Commons as part of society-wide infrastructures.

The work of ZenDis in particular is very important. It supports the adoption and use of open source technologies through German public administrations by making it easier for them to start using and contributing through their regulated public sector co-development platform, Open CoDE, a mirrored instance of GitLab. Theirs is a model which might be highly relevant for other governments looking to adopt and contribute to open source projects as Digital Commons.

The future of OSPOs and Digital Commons

These lessons from the conference show how OSPOs might play a role in defining rules and governance of Digital Commons projects, as well as invest in them and use them at scale providing society-wide infrastructure. Building on the precedents set by governments like France, Netherlands, Germany, and Czechia, Digital Commons can be one of the many priorities for government OSPOs as they work to help adapt open source technologies and principles to the needs of public sector institutions.

That said, it is an open question if a mature open source participant organisation should have an OSPO to centralise open source/Digital Commons expertise or that expertise should become ingrained across the whole organisation. OSPOs represent the thinking that open source is special, exciting and new, which can help catalyse open source adoption and reuse. However, the desired end state might instead be one where it is deeply embedded across public sector institutions and is a normal and regular part of engineering good practice.

Right now, it is clear that not all governments have these capacities just yet. Without capacity-building, it will be challenging for governments to build OSPOs that adequately support and sustain Digital Commons, as there will be delays in implementing open source technologies and building out necessary digital infrastructure. Other governments will likely need to undertake similar efforts as they seek to build their OSPOs. In these cases, though, OSPOs will need to work with governments to help address bottlenecks and capacity issues, while also creating the necessary political will, before work can be done.

One learning from the German case is just that; that one of the preconditions for their success was to build in-house intelligence and capacities first, which helped them understand key dependencies, catalogue available solutions, identify software development needs, and conduct strategic investments. The need for capacity-building is also in line with efforts like the EU’s OSPO, which created the Open Source Observatory (OSOR) as a way to socialise knowledge about open source adoption and use across European public administrations.

We hope some of these observations might bear fruit and look forward to tracking the growth of OSPOs in Europe and beyond in the years to come!