Co-authors: Nicholas Gates (OpenForum Europe, NGI Commons partner) and Emrys Schoemaker (Caribou Digital, DCTF Member)

Digital infrastructure is increasingly recognised as the ‘rails’ on which our digital futures run, with recent news drawing attention to the expanding role of digital infrastructure and the interests it serves. From recent stand-offs between Brazil and X and efforts to take TikTok into American ownership, all the way to multilateral attention to digital infrastructure in the the Global Digital Compact and the DPI Safeguarding Agenda, digital infrastructure is front of mind.

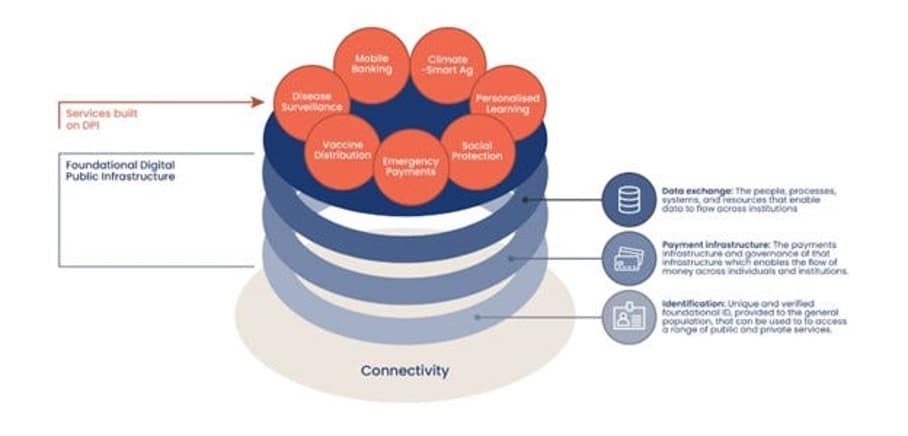

For governments, Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) – a narrower understanding of digital infrastructure for governments – has emerged as a significant way for thinking about public sector digital transformation by promoting common ‘rails’ for digital service delivery. So, what is DPI exactly?

The evolution of the term DPI

The understanding of DPI has evolved rapidly since 2021. Today, it is defined quite broadly and different actors have different definitions of it.

A commonly used definition for DPI is the one adopted by the G20 under India’s Presidency, which describes it as “a set of shared digital systems that should be secure and interoperable, and can be built on open standards and specifications to deliver and provide equitable access to public and / or private services at societal scale and are governed by applicable legal frameworks and enabling rules to drive development, inclusion, innovation, trust, and competition and respect human rights and fundamental freedoms.” Regardless of variations, most actors focus on three capabilities in particular: digital identity, data exchange, and digital payments.

The rapid growth in attention to DPI culminated in the Global DPI Summit, which took place from October 1-3 in Cairo, Egypt this year. The goal of the Summit – which was co-hosted by the United Nations, World Bank, the Ministry of ICT Egypt and funded by Co-Develop Fund – was to ‘spotlight the extraordinary progress countries are making in adopting and implementing DPI principles’.

How to understand DPI today?

Advocates and builders of DPI often make no distinction as to who develops those capabilities or their licensing, despite the concept of DPI emerging alongside Digital Public Goods (DPGs). DPGs are defined as ‘open-source software, open standards, open data, open AI systems, and open content collections that adhere to privacy and other applicable laws and best practices, do no harm, and help attain the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)’.

Like with DPGs, most accounts of DPI emphasise its promotion of public value, advocating for an enlarged and leading role from the public sector in building, maintaining and contributing to these most foundational and critical capabilities.

But while ‘DPGs for DPI’ has emerged as a common rallying call, discussions at the DPI Summit in Cairo suggested that for many working in the DPI space, there is a greater role for the private sector than DPG advocates previously imagined.

This was epitomised by Pramod Varma, founder of the Centre for Digital Public Infrastructure and one of the lead architects of the India Stack, describing DPI as ‘public rails for private innovation’. Additionally, proponents of DPI have argued for interoperability as a key feature for delivering public interest and value, but we should anticipate tensions between this and the interests of the private sector. This is particularly true in the context of Big Tech hyperscalers like Google, Microsoft and Amazon who are increasingly looking to sell DPI-as-a-service; or, as some have called it, ‘DPI in a Box’.

Moreover, while the DPI approach certainly enables some of the ‘public’ attributes identified above – in the interests of offering accessible solutions to countries with limited capacity – there has been a move to offer solutions that are either offered as a packaged solution (e.g. DPI in a Box) or have a level of complexity (for example MOSIP) that requires a reliance on system integrators. Both of these factors introduce new dependencies on server providers or systems integrators, creating more opportunities for vendor lock-in (which the DPGs movement has sought to avoid).

A commons-based approach to DPI?

For this reason, the NGI Commons Consortium believes that Digital Commons – particularly the conception of Digital Commons being offered by Europe – offers a long-term strategic opportunity for Europe in its engagement with the promotion and development of DPI globally. (Note: We presented some early thinking in this area at the Global DPI Summit, where NGI Commons sponsored a Dialogue Session on ‘Emerging Opportunities for Digital Commons as DPI: Lessons from Europe’, seen in the photo below.)

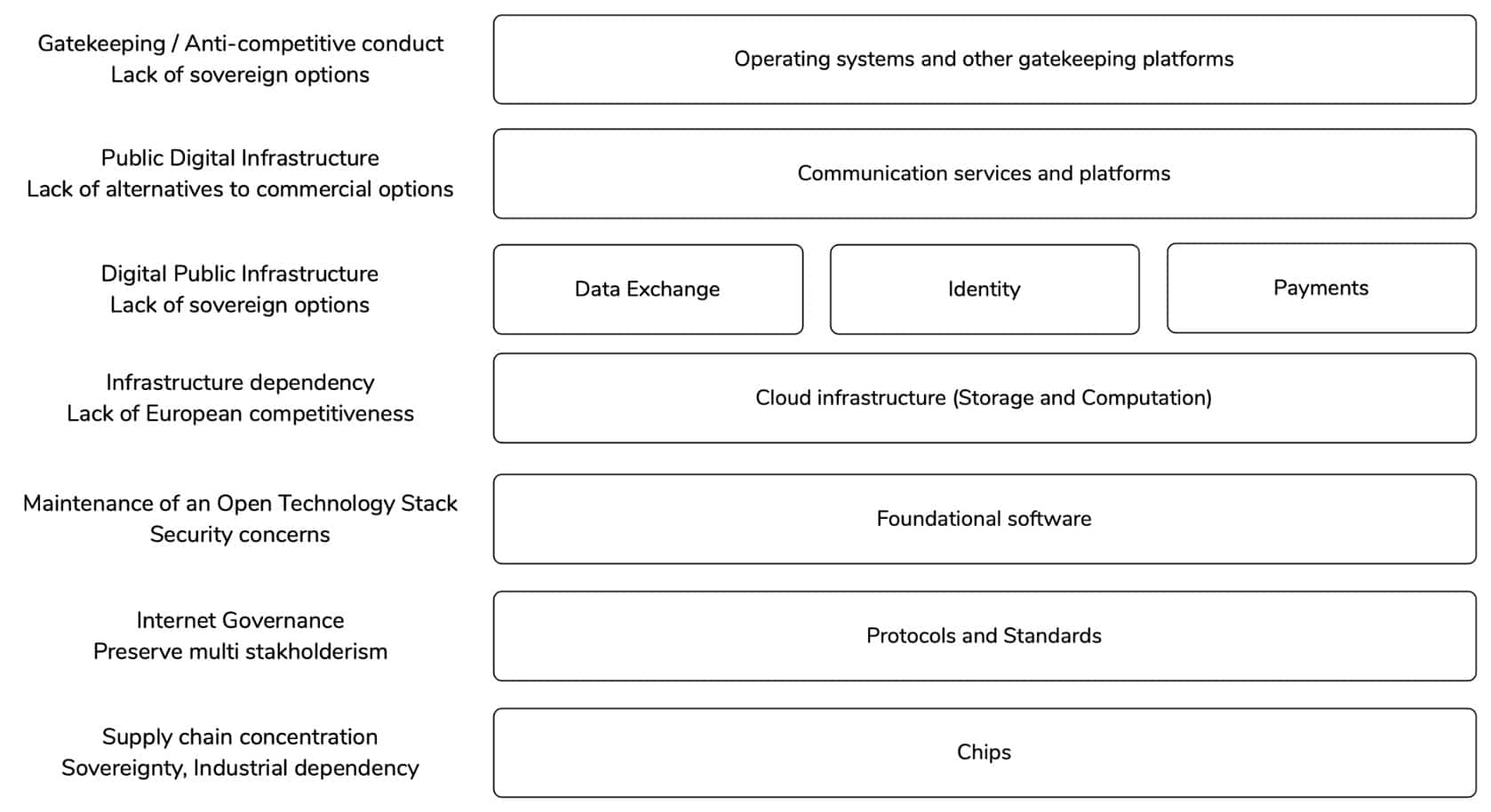

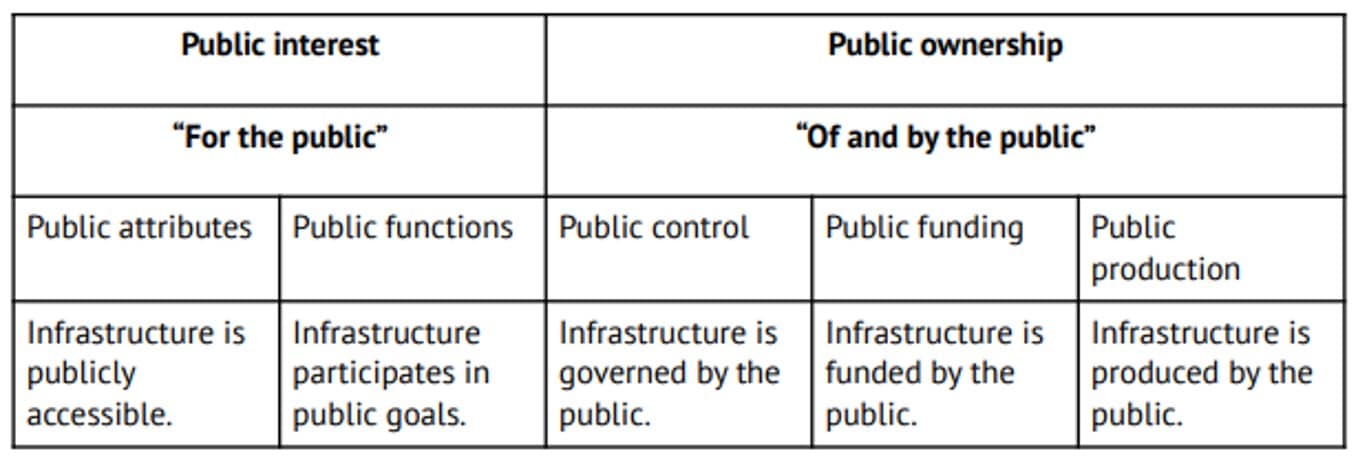

In his recent paper for Open Future and NGI Commons, Jan Krewer makes the argument for Digital Commons as providers of all types of ‘public’ digital infrastructures (PDI), not just those owned by the state or those foundational digital government capabilities, which would be considered as DPI. Krewer argues that there is an essential role for understanding Digital Commons as promoting the community contribution and governance to shared digital resources, not least because of the increasingly centralised nature of many DPIs, including IndiaStack.

The paper argues that a commons-based approach might be additive to the debates around DPI, and indeed all layers of PDI more broadly (see above). Compared to DPI, the idea of PDI emphasises a conception of public interest and public ownership which prioritises sovereignty and independence, as well as better guarantees public interest and public ownership across various attributes (as seen below). We see the values underpinning PDI as ones which might help elevate the public element of DPI, and the types of technologies used to build the digital government capabilities that constitute DPI.

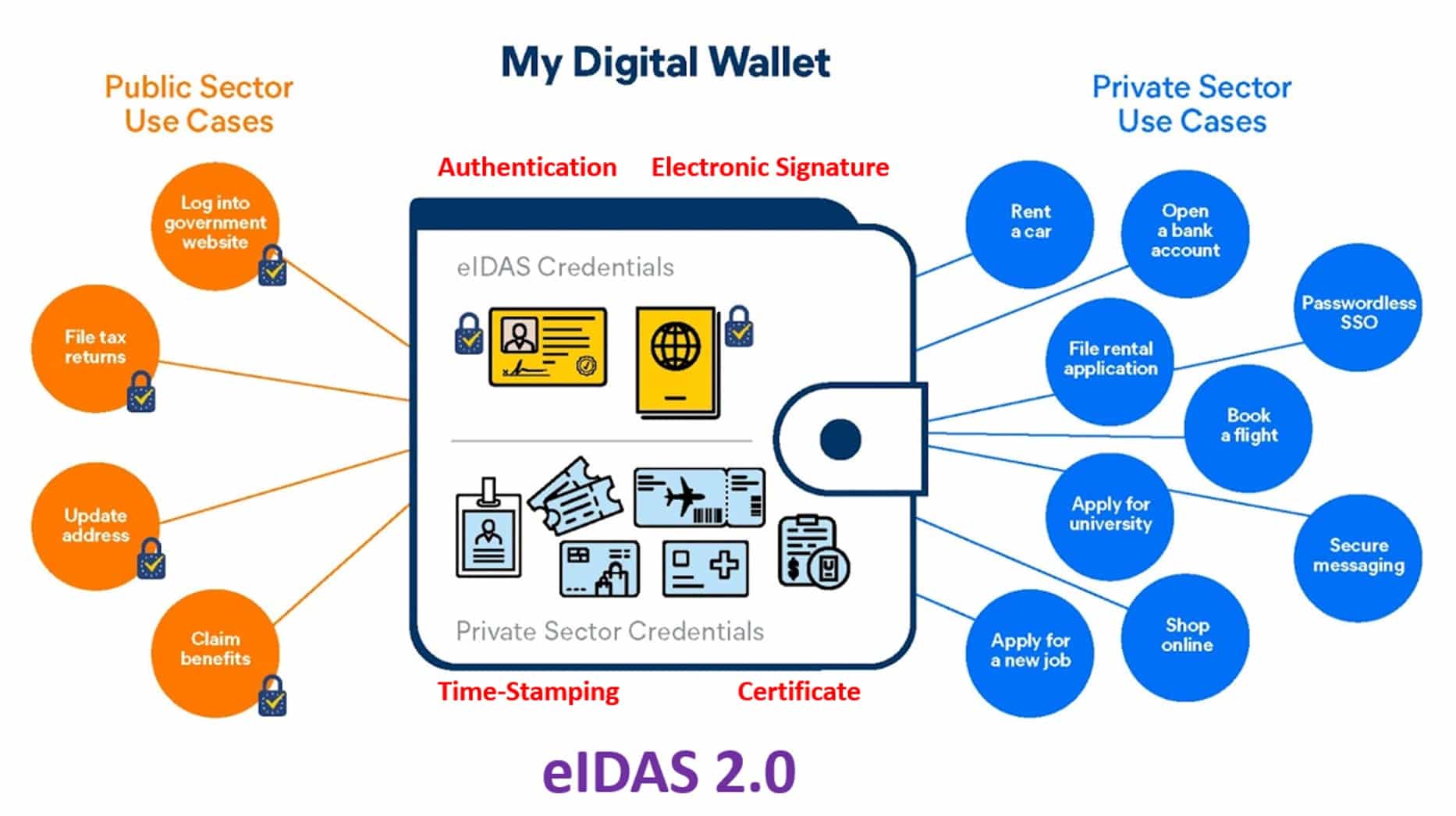

This is not just theoretical. There are many examples of the Digital Commons approach supporting European-led projects which can be regarded as DPI. Despite being underrepresented in fora like the Global DPI Summit, Europe is demonstrating that better governance of technology with more autonomy and choice is possible. For example, the development of the new identity regulation eIDAS 2.0 specifies open standards for a digital wallet that enables citizens to control their data.

Conceptualising a European approach to DPI

A European approach to DPI, which would inherently be supranational, could include but go beyond existing conceptions of DPI by creating open capabilities which offer more choice and autonomy to European Member States when provisioning infrastructure. Focusing on sovereignty and independence requires an expansion of the concept to include the full digital value chain – from chips to cloud, if you like. And it would be a central part of Europe’s effort towards growth, as argued for in the Draghi report.

But it would also require a ‘core DPI element’ as well.

Building on projects like eIDAS 2.0, Gaia-X, the European Open Science Cloud, and the digital euro, a truly European approach to DPI could be one which establishes a foundational European “stack” of core elements, not just payments and data exchange, to be leveraged by governments should they so choose. (A good example in this regard is the Common European Data Spaces, a European initiative focused on “digital building blocks” for data exchange.) This proposed ‘stack’, while defined differently depending on who you ask, is an idea supported by DG-CNECT as an Open Internet Stack and advocated (with slightly different emphasis) by the European Parliament. In theory, it would be comprehensive and allow for Member State governments to build on top of and innovate around the core.

As emerging economies like India and Brazil showcase their models of DPI, there is an increasing need for the European Commission (EC) to engage more in these global policy debates. A change in vocabulary is already beginning. Increasingly, individuals representing EC-led or EC-backed projects like the e-ID Frameworks and Open Wallets have begun using the term DPI in relation to the promotion of large-scale, EU-funded technology initiatives. But, it hasn’t added up to a European-wide policy on DPI (at least not yet).

Where do we go next?

In this vacuum, we argue that Europe has an unrealised strategic advantage when it comes to engaging with external debates on designing and governing DPI. Going forward, the Commission can and should continue to play a constructive role in the debates on DPI, offering more choice to its Member States in how DPI is provisioned and engaging more forcefully in global conversations, particularly around a conception of DPI that prioritises openness and independence. In particular, it could offer more open alternatives to its Member States for provisioning foundational government capabilities.

These ‘open alternatives’ are where Digital Commons might make a difference. EU values associated with Digital Commons might help reinforce the idea of a truly whole of society ‘public’ and not just ‘public sector’ services and ownership, while still allowing for strong and leading contributions and innovation from the public and private sectors. In addition to a comprehensive industrial strategy as per Draghi, by amplifying the likes of Gaia-X, the EU Digital Identity Wallet, and even the digital euro as Digital Commons, the EU can help offer more open alternatives for the public sector, and support them at commensurate levels.

Not only that, but a conception of a ‘European DPI’ or a ‘EuroStack’ that is more aligned with our understanding of Digital Commons would support the European Commission’s case for developing digitally sovereign infrastructure. The people of Europe need digital infrastructure that serves the public interest, and as Emrys Schoemaker (co-author of this article) notes in a recent piece, it ‘requires a holistic approach that integrates governance, technology, and markets to ensure the building of digital infrastructure that serves the common good’.

It would also be in the strategic interest of Europe to invest in Digital Commons as alternatives for building DPI. Geopolitics are being conducted through technology – from China’s ‘Digital Silk Road’ to India’s championing of DPI – and apart from the German support of GovStack, Europe is best known for the regulatory based ‘Brussels effect’. A recent discussion hosted at ECDPM argued that Europe could champion an approach to digital infrastructure that aligns with EU standards, systems and values and promotes national sovereignty and independence, offering global partners systems and standards that enable access to EU markets as well as strengthening autonomy and choice.

The specifically Digital Commons-led understanding of DPI would put it back under the umbrella of ‘public’ digital infrastructure, while packaging or bundling Digital Commons as foundational capabilities for all Member States. This will require a cross-Commission effort to coordinate the efforts of multiple Directorate-Generals – most notably those for Communications Networks, Content & Technology (CNECT) and International Partnerships (INTPA) – and continually engaging with global actors and civil society.